Disunited Nations

As it celebrates its 80th birthday with cutbacks and sackings, is it time for the UN to retire?

On Sept. 15, at the height of the UN’s 80th anniversary celebrations, and just one week before 140 heads of state descended on New York for the General Assembly’s annual debate, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres dropped a personally signed bombshell on all 130,948 of his colleagues.

As the word “frankly” in the opening paragraph of his three-page letter made clear, this was not an invitation to attend a UN 80th birthday party.

As staff in New York and UN offices around the world anxiously scanned the message for a punchline, certain phrases jumped off the page: “targeted efficiencies,” “cost reductions” and “measures to improve the management and operations of the Secretariat.”

The details of the bad news could be found in the third paragraph: The core budget of the UN Secretariat in New York for 2026 was to be cut by about 15 percent — more than $500 million — and one in five jobs there were to be axed, plus 13 percent of peacekeeping-support posts on top of that that.

This was the latest manifestation of Guterres’ “UN80 Initiative,” a program launched in March that is designed to ensure the organization becomes “more agile, integrated, and equipped to respond to today’s complex global challenges amid tightening resources.”

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres launching his UN80 reforms on March 12, 2025. (Getty)

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres launching his UN80 reforms on March 12, 2025. (Getty)

In his letter to staff, Guterres sounded like every CEO who has ever had to slash jobs under pressure from shareholders — or, in his case, from one key stakeholder among the UN’s 193 member states.

“For some colleagues,” he wrote, “these changes may mean relocation for themselves and their families” or “changes in functions or reporting lines.”

For others, he added, slipping even deeper into HR jargon, the changes would mean “separation from service.”

The UN, he added, was “committed to supporting staff through this transition … support measures are in place for those whose posts are affected,” and discussions would take place “with compassion and frankness.”

Richard Gowan is the program director for global issues and institutions at International Crisis Group. He oversees its advocacy work at the UN and regularly liaises with diplomats and UN officials in New York. Right now, he said, “there are two levels of bleakness” within the global organization.

“On the one hand, everyone is suddenly facing the possibility that their job is about to disappear,” he said. “If you spend time at the UN and ask how people are doing, they’ll tell you about their concerns about mortgages and schooling and so on.

“But that almost obscures the much more fundamental sense that the future of the institution as a political actor in the world is in doubt.

“Talking to diplomats, who are not so much affected by the budget cuts, they say, ‘We continue to go through the motions. We continue to try to get resolutions, we continue to try to defend UN norms at a time when a lot of countries are denying them. But we just don’t know what this institution is going to look like, or even if it can survive this moment in global politics.’”

The UN Charter was signed in San Francisco on June 26, 1945, by representatives of 50 countries who attended the United Nations Conference on International Organization. It came into force on Oct. 24 that year, a day observed annually since then as United Nations Day.

The founding conference of the United Nations, held in the San Francisco Opera House in 1945. (Getty)

The founding conference of the United Nations, held in the San Francisco Opera House in 1945. (Getty)

Foremost among the organization’s founding champions was US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who coined the name “United Nations.” However, he would not see the organization for which he fought come into being; he died just two months before its charter was signed.

But in an address to the conference in San Francisco on April 25, 1945, two weeks after Roosevelt’s death, his successor, President Harry S. Truman, urged the delegates to adhere to his predecessor’s “lofty principles.”

Speaking only days before the surrender of Nazi Germany in Europe, and while the Second World War continued to rage in the Far East, Truman evoked the memory of the millions who had died in two global wars.

“Let us labor to achieve a peace which is really worthy of their great sacrifice,” he said. “They died to ensure justice. We must work and live to guarantee justice — for all. We must make certain, by your work here, that another war will be impossible.”

The task facing the delegates, he added, was for them to be “the architects of the better world” and “a just and lasting peace.”

But instead of joyously celebrating its eighth decade this year, the UN is fighting for its very existence in a world that is very different from the one into which it was born 80 years ago, and under increasing pressure from an American president very different from the one who helped to bring it into existence.

Nothing illustrated this more clearly than the speech America’s current president, Donald Trump, delivered to the 80th UN General Assembly on Tuesday, Sept. 23.

“What is the purpose of the United Nations?” President Trump asks the UN General Assembly on Sept. 23, 2025. (Getty)

“What is the purpose of the United Nations?” President Trump asks the UN General Assembly on Sept. 23, 2025. (Getty)

Much of his speech, which overran his allotted 15-minute time slot by about 45 minutes, was devoted to some of his pet themes — mostly a litany of his multiple claimed successes, at home and abroad, and a few of his bugbears.

In just seven months, he told his fellow world leaders, he had “ended seven unendable wars.” For doing so, he added, “everyone says that I should get the Nobel Peace Prize” (which, incidentally, has been awarded to UN personnel and agencies 11 times since 1950, and to four US presidents and one vice-president since 1906.)

The president’s speech was wide-ranging.

The COVID-19 pandemic was caused by “reckless experiments overseas.”

Climate change was “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world” and “all of these predictions made by the United Nations and many others, often for bad reasons, were wrong. They were made by stupid people.”

As for “falsely named renewables … they’re a joke,” said Trump. “They don’t work.”

But at the heart of the speech was a series of astonishing attacks on the UN itself. It had failed, he said, to help him while he was busy ending seven wars.

“I never even received a phone call from the United Nations offering to help in finalizing the deals,” he complained. So “what is the purpose of the United Nations?”

The organization, he added, “has such tremendous potential. I’ve always said it … But it’s not even coming close to living up to that potential for the most part, at least for now; all they seem to do is write a really strongly worded letter and then never follow that letter up.”

French President Emmanuel Macron and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas at the 79th General Assembly in 2024. This year Abbas was refused a visa by the Trump administration. (Getty)

French President Emmanuel Macron and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas at the 79th General Assembly in 2024. This year Abbas was refused a visa by the Trump administration. (Getty)

Then he turned his attention to Gaza and the recent flurry of moves by nations, led by France and the UK, to officially recognize a Palestinian state, which had preceded his appearance at the UN.

“As if to encourage continued conflict, some of this body is seeking to unilaterally recognize a Palestinian state,” Trump said, before pivoting, confusingly, to accuse the UN of “funding an assault on Western countries and their borders … The UN is supposed to stop invasions, not create them, and not finance them.”

That last comment earned more than a few puzzled looks around the chamber, but the word “finance” hit home, not least among members of the UN Secretariat wondering when, if ever, America would get around to paying the long-overdue funding it owes the organization.

Guterres launched his UN80 reform initiative in March. A massive exercise in cost-cutting and reorganization, it is ostensibly a response to the “liquidity crisis” that has dogged the UN for the past seven years, but is also widely viewed as an attempt to placate Trump.

As of Sept. 15 this year, only 129 of the UN’s 193 member states had paid their contributions toward the organization’s $3.72 billion general budget for 2025, which was approved in December 2024 by the General Assembly.

UN financial regulations dictate that to keep the UN functioning properly, all contributions must be paid by Feb. 6 each year. In 2025 only 49 states complied with this requirement. Over the following seven months, payments dribbled in from a further 80 states.

But of the 64 nations whose contributions remain overdue, one stands out: the US, the country that in 1945 helped to give birth to the UN and which, ever since, has been the organization’s largest single funder.

Until now.

Responsible for about a fifth of the UN’s regular budget and a quarter of its peacekeeping funding, the US is also responsible for much of the organization’s ongoing liquidity problems.

A French peacekeeper with the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) in August 2025. (Getty)

A French peacekeeper with the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) in August 2025. (Getty)

Each country’s contribution to both budgets is based on a complex formula designed to assess its “capacity to pay.” A report in May by the UN’s financial controller revealed that the US owed about $1.5 billion in unpaid dues to the regular budget, and a further $1.5 billion to the peacekeeping fund. This is three times as much as the next-largest defaulter, China, which owes about $590 million to both of those budgets.

As Controller Chandramouli Ramanathan told the General Assembly in July, cash shortages caused by late or non-paying states meant approved peacekeeping budgets had to be slashed.

It was a case of simple math, he said: “No money, no implementation. There is not enough cash.”

The general budget funds UN programs across a number of key areas, including political affairs, international justice and law, regional cooperation for development, human rights and humanitarian affairs.

UN peacekeeping operations are funded through a separate account. In July, the General Assembly approved a budget of $5.38 billion for 2025-2026, and about 70,000 military, police and civilian personnel currently are deployed to 11 peacekeeping missions across Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

The UN now faces the very real prospect that, in an increasingly isolationist world, its biggest single funder might withdraw altogether from an organization to which it is clear the current administration in Washington is ideologically and politically opposed.

Since taking office in January, Trump has withdrawn the US from the World Health Organization and UNESCO. He has also ordered an end to US funding of other UN agencies, including the Human Rights Council and UNRWA, the agency that provides aid and support for Palestinian refugees.

A statement from the White House on Feb. 4 made clear the motivation for this.

“The United States helped found the United Nations after (the Second World War) to prevent future global conflicts and promote international peace and security,” it began.

“But some of the UN’s agencies and bodies have drifted from this mission and instead act contrary to the interests of the United States while attacking our allies and propagating antisemitism.”

It added that UNESCO, a globally respected organization created in 1945 with the mission to foster peace worldwide through international cooperation in education, science, culture and communication, had “continually demonstrated anti-Israel sentiment over the past decade.”

No evidence of this was provided in an extraordinary statement that could have come straight from Tel Aviv.

It is also clear that the UN, which in theory is an independent organization answerable not to one member state but to all, is seen as just another target for the Trump administration’s escalating culture wars.

UN headquarters in New York – under siege by the Trump administration. (Getty)

UN headquarters in New York – under siege by the Trump administration. (Getty)

In a statement to a UNICEF board meeting in February, a representative of the US Mission to the UN all but ordered the organization to eradicate “terms and concepts that conflict with US policies as set out in President Trump’s recent Executive Orders.”

The specific target was “Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility programs (which) violate the text and spirit of our laws by replacing hard work, merit and equality with a divisive and dangerous preferential hierarchy.”

The talk in the corridors of UN headquarters in New York is of sitting out the siege. Trump’s second, and constitutionally final, term in office expires in January 2029; perhaps a more amenable, more globally minded US president will succeed him.

But behind the UN’s budgetary and Trumpian ideological difficulties, far bigger questions are being asked about its role in the modern world.

The first meeting of the UN Security Council, in 1946. It's operation has been hampered ever since by the veto demanded by each of the five permanent members. (Getty)

The first meeting of the UN Security Council, in 1946. It's operation has been hampered ever since by the veto demanded by each of the five permanent members. (Getty)

“If you go back over the history of the organization, there have been many moments when the financial situation has been very hard, and there have also been moments when big-power tensions have paralyzed the Security Council,” said Gowan.

“But there is a very deep sense of crisis around the organization now. We face a set of circumstances which raise very big questions about the long-term future of the organization, and we’re seeing the convergence of at least three profoundly worrying trends.”

The first of these is the deterioration of major-power relations, “which are paralyzing the Security Council but are also spreading into other parts of UN business.”

Secondly, Gowan said, the US funding cuts “have revealed just how dependent a lot of the UN has become on American financial support, especially the humanitarian operations, and without that financial support it is just going to have to shrink.

“Then lastly, less discussed at the moment but in the background, there is a growing realization that some of the really big UN pledges of recent times, such as the Paris climate-change goals and the Sustainable Development Goals, are just not going to be met.”

The climate targets set at COP21 in Paris in 2015 will not be hit as planned by 2030. (Getty)

The climate targets set at COP21 in Paris in 2015 will not be hit as planned by 2030. (Getty)

It is almost 10 years since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in France during COP21, the UN Climate Change Conference, and 10 years since the Sustainable Development Goals were adopted. Both are supposed to hit their ambitious targets by 2030.

“Those are meant to be the really big global commitments that would bind the UN together, and it’s now very clear that we’re not going to end extreme poverty by 2030 and we’re not going to keep global warming under the Paris target,” said Gowan.

“Even looking beyond the current moment of crisis, that raises a lot of questions about what good UN diplomacy does, and all of this is now coming together at once.”

There are 17 Sustainable Development Goals and not one of them is on course to be achieved by 2030, said Margaret Williams, the associate director of SDG16+ at New York University's Center on International Cooperation (CIC).

SDG16+ is a term championed by the Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies initiative, a coalition of countries, international organizations and civil society groups hosted by the CIC. The idea behind it is that success in achieving the objectives of SDG16 — which relate to peace, justice and strong, inclusive institutions — is essential for achieving all the other SDGs.

Not one of the Sustainable Development Goals set in 2015 is on target to be achieved. (Getty)

Not one of the Sustainable Development Goals set in 2015 is on target to be achieved. (Getty)

“There is now a 35 percent on-course record across the SDGs, and SDG16 is one of a few for which none of the targets are on track,” said Williams.

Nevertheless, she rejects the suggestion that it is now impossible to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

“I think we are in an incredibly challenging space,” she said. “We have just five years left until the 2030 benchmark and we’re at the 80th anniversary of the UN and we’re in the midst of these very significant reforms … The sense of fragility and uncertainty is global, and where multilateral institutions will be, in terms of these reform processes and in terms of reaching sustainable development objectives, remains to be seen.”

What will happen to the SDGs after 2030 also remains unclear.

“There are a couple of different ideas out there,” Williams said. The future course could be shaped at any one of a series of upcoming milestone meetings, including the UN’s Second World Summit for Social Development, which will take place in Doha this November.

But the important thing right now, she believes, is to remain positive and constructive.

“If your approach is, ‘Well, we failed. Next!’, you end up losing sight of where progress has been achieved, and what that progress has meant for people’s lives, and this is basically what we try to focus on,” Williams said.

“This not to negate the failures, but it’s to say that there are areas of progress and areas where people’s lives have been improved. And if you end up being apathetic, throwing your hands up, then you’re failing additional people.”

What the UN’s post-2030 SDGs landscape is going to look like “isn’t clear,” she continued. “Discussions are being had, whether in the open or behind closed doors.

“But if you look at what makes a difference in people’s lives, and at what makes sustainable development sustainable, you can’t put SDG16 on the chopping block.”

However, the future for the UN and its major projects is undoubtedly uncertain.

UN SECURITY COUNCIL VETOES

Since February 1946 Security Council resolutions have been blocked 326 times by one or other of the five permanent member countries exercising its right to veto; 87 vetoes have concerned events in the Middle East.

International politics and the UN “are both at an inflection point right now,” said Eugene Chen, a former director of the Prevention, Peacebuilding, and Protracted Crises program at the Center on International Cooperation.

Also a former lead negotiator for the US government at the UN on topics including peacekeeping financing, he knows his way around the corridors of the organization’s New York headquarters.

“Do I believe that UN reform is necessary? Absolutely, and I think this is the time to do it,” he said. “But do I think UN80 is what will deliver it? I would have to say no.”

He believes the present reforms are “fundamentally based on an incorrect understanding about the roots of this current US administration’s way of thinking about the world and about the UN.

“The UN80 initiative was conceived back in February, a few weeks after the Trump administration had issued its executive order calling for a 180-day review of US participation in the UN and international agreements.

“It was also at the height of the DOGE efforts to cut down the US federal government as well, and so I think that the initiative was conceived by the secretary-general as a way to try to head off similar cuts and attacks on the UN, by trying to demonstrate to the US government that he was committed to reform and to cost-cutting.

“But as we have seen in the past few months, that theory is fundamentally flawed. The US very clearly still wants to cut down the UN, and we have also seen that the administration has not only zeroed out its contributions to the UN going forward, but it has also canceled all the previously appropriated funds for the UN.”

Amal Mudallali was Lebanon’s ambassador to the UN from 2018 to 2022 and served as vice-president of the General Assembly in 2020.

“It’s true that the United Nations is now facing its most difficult and challenging time since it was established in 1945, and that’s because it is a reflection of our world today,” she said.

“The UN is the collection of the member states, and our world is in turmoil. Uncertainty is the most prevalent state of affairs now. Conflicts are proliferating all over the world, poverty and inequality is on the rise everywhere and the climate crisis is challenging people and threatening lives everywhere.”

The challenges, she said, “are huge. But the United Nations that was established to fix these problems is now facing an existential threat because of the way the great powers are dealing with it.

“The great powers that established this organization, to save humanity from the scourge of war, are now undermining its mandate by working outside the UN system to try to create spheres of influence around the world that are not conducive to multilateralism or to creating an atmosphere of peace, prosperity and development.”

The very founders of the UN “are now moving away from multilateralism and going into more bilateral and regional groupings that are more nationalistic,” Mudallali said.

The most alarming recent manifestation of this trend, she added, was the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit at the beginning of September, attended by Russian president Vladimir Putin and other world leaders, during which Chinese President Xi Jinping declared that “global governance has reached a new crossroads.”

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in September 2025: a challenge to the UN-based world order. (Getty)

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in September 2025: a challenge to the UN-based world order. (Getty)

“This is the most important challenge to the international system that the United Nations was based on that we’ve seen for a long time,” Mudallali said.

There is, she added, no case that can be made for dismantling the UN.

“If you didn’t have the UN, you really would have to invent it,” she said. “But we are lucky enough that this organization, after 80 years, is still an important place where people can sit down and talk and argue and disagree, but at the same time still work together and bring out results.”

Mudallali remains hopeful that the secretary-general’s UN80 program of reforms will resolve some of the internal problems “that are giving some powers justification for cutting their budgets, saying: ‘The UN is corrupt, the UN is this and that.’ They’re cutting budgets. They’re cutting programs. They are streamlining things and there’s a lot of redundancy they’re trying to work on.

“I really hope that they succeed in that, because everything now depends on becoming more credible, convincing the world that things are going to be on the right track.”

But she is concerned about the steady erosion of the UN’s peacekeeping role.

“You don’t want the UN to be only a humanitarian organization,” Mudallali said. “The most important part of it is its peace and security function, and for the past few years the big powers have been sidelining the UN in this role. That’s not acceptable, because that takes away from the UN its main role as an organization that’s entrusted with maintaining peace and security around the world.”

Protests against UN inaction in Burundi after the massacre of Tutsi refugees by Hutu rebels in August 2004. (Getty)

Protests against UN inaction in Burundi after the massacre of Tutsi refugees by Hutu rebels in August 2004. (Getty)

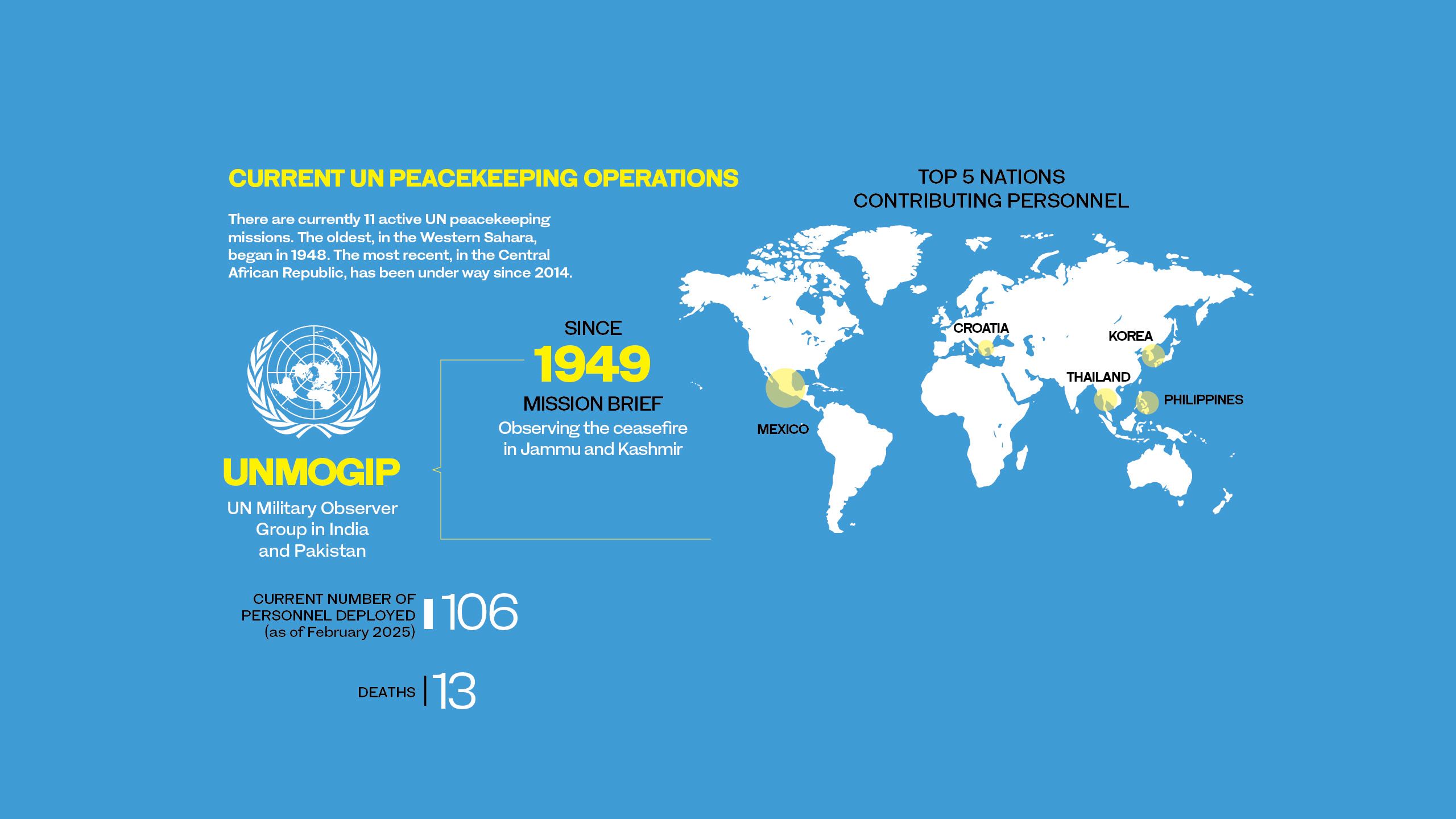

The UN currently has 11 peacekeeping operations in progress, one of which, in Jerusalem, has been running for an astonishing 77 years. Introduced in May 1948, the UN Truce Supervision Organization was the first UN peacekeeping operation. Its military observers have remained in the Middle East ever since, monitoring ceasefires and supervising armistice agreements.

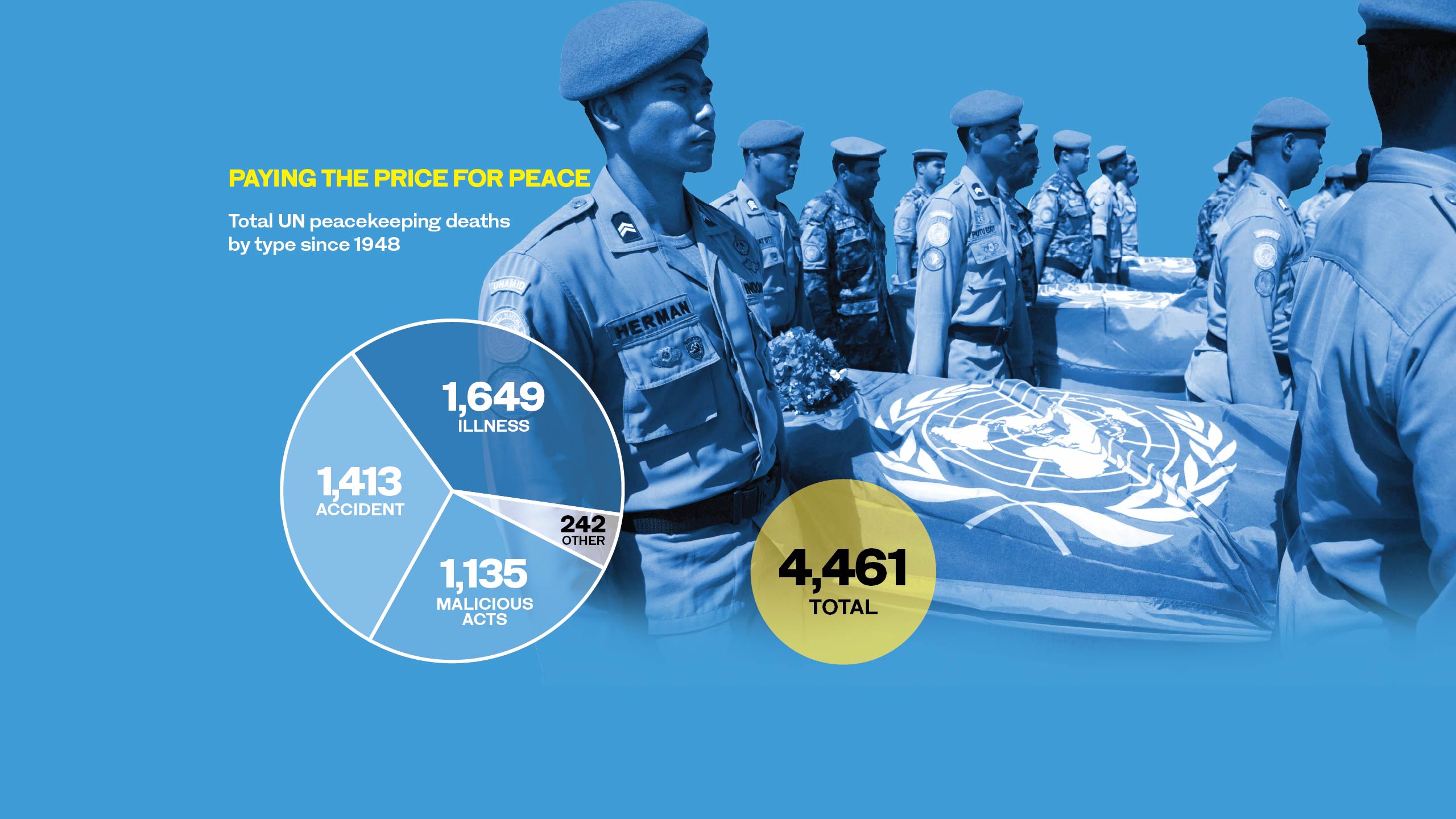

UN peacekeeping comes at a great cost, in terms of lives as well as money. Since 1948 4,451 peacekeepers have been killed on UN missions. The UN Interim Force in Lebanon, which was established in 1978 and remains active, with more 10,500 personnel deployed, has suffered the single highest number of casualties: 339 deaths as of Aug. 31 this year.

In one of the latest attacks on the force, on Sept. 3 Israeli drones dropped four grenades near troops clearing a roadblock that was preventing access to a UN position. On that occasion no one was hurt.

The incident happened just days after the Security Council, apparently bowing to pressure from Israel and the US, called time on UNIFIL, voting to end its operations by the end of 2026.

When it comes to casualties during UN operations, there is an uncomfortable reality that is rarely openly discussed.

“Since the end of the Cold War, developing countries have become the largest contributors of troops and police to peacekeeping operations, and they also have been the ones that generally provide infantry,” said Chen.

Unsurprisingly, they are also the ones who suffer the most casualties.

For some countries, the decision to provide troops for UN operations is financially driven.

“There are reimbursements that are provided to troop-contributing countries, and it’s a flat rate for all countries,” said Chen.

“That means that for a lot of low-income countries the reimbursements they receive are much higher than the costs they incur.”

This explains why the countries that have suffered the highest number of deaths among troops while on UN operations include India (182), Pakistan (171), Bangladesh (168), Nigeria (160), Ghana (156) and Ethiopia (141).

Pakistani UN troops in Congo, October 2003. Pakistan has suffered the second highest number of deaths on UN peace missions. (Getty)

Pakistani UN troops in Congo, October 2003. Pakistan has suffered the second highest number of deaths on UN peace missions. (Getty)

The results of UN peacekeeping operations have been mixed over the years.

“No one has any difficulty listing the failures,” said Gowan. “Everyone remembers Rwanda, Srebrenica and Somalia. But I think people forget the successes, which are treated as routine.

“If you look around the world, you have places such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, Timor-Leste, Cambodia, where UN peacekeeping actually did stabilize countries after prolonged conflicts and did enable democratic transitions.”

But now, he added, “one is incredibly distressed seeing the UN failing in so many places. If you’ve been working, as I have, up close on the Security Council for the past five years, you’ve seen the UN fail in Myanmar, fail in Ethiopia, fail over Ukraine, fail over Gaza, fail over Sudan, and in the meantime even mishandle other situations where, really, it should have been able to get a grip, like Haiti.

“This is all really very distressing. It’s not a job that necessarily sends you home full of good cheer.”

Despite escalating conflicts around the world, including in Ukraine and Gaza, it is remarkable that no new UN peacekeeping operation has been established in a decade. One reason for this, said Chen, is cost.

“Missions that were deployed since the end of the Cold War have been very large and very expensive, many of which had annual budgets of over a billion dollars,” he explained.

“So after reaching a high-water mark in about 2015, when peacekeeping budgets exceeded $8 billion, we’ve definitely seen a bit of a retrenchment because of fatigue over those costs.”

But he added: “I think there’s another real issue here, which is that Secretary-General Guterres has not been interested in peacemaking. Secretaries-general used to shuttle around and try to facilitate and negotiate ends to conflict across the world, but Guterres has not been interested at all in that

“The only times when the UN has engaged in high-profile negotiations over the course of his tenure has been to deal with the spillover effects of conflict, but not with the conflicts themselves.”

In 2022, the UN stepped in to facilitate the Black Sea Grain Initiative in an attempt to deal with one of the side effects of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But it has not intervened to help resolve that conflict itself.

Similarly, in 2023 the UN coordinated an operation to remove more than a million barrels of oil that threatened to leak from a decaying tanker moored for years off the coast of war-torn Yemen, but has failed to address the conflict between the Houthis and the country’s internationally recognized government.

The abandoned oil tanker Safer during operations in June 2023 to prevent its cargo leaking into the Red Sea. (Getty)

The abandoned oil tanker Safer during operations in June 2023 to prevent its cargo leaking into the Red Sea. (Getty)

“It’s been so notable that (the secretary-general) has simply not even attempted to insert himself in any of these high-profile conflicts,” said Chen.

“There will be a comment from the press secretary or the spokesperson, and sometimes comment from the secretary-general, but there’s no kind of engagement in shuttle diplomacy, the dispatch of a personal envoy, or anything like that. That would have been just the normal course of business under previous secretaries-general.”

The absence of the UN in a peacekeeping capacity has been most striking in Gaza. On Sept. 16 this year, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, which was established by the UN Human Rights Council in 2021, concluded: “On the basis of fully conclusive evidence … statements made by Israeli authorities are direct evidence of genocidal intent.”

It added: “Genocidal intent was the only reasonable inference that could be drawn based on the pattern of conduct of the Israeli authority” in Gaza, where Israeli forces have killed more than 60,000 people in the past two years.

But the UN has focused solely on the humanitarian mission in Gaza, where 400 of its own staff have been killed by Israeli attacks since October 2023.

A UN worker amid the rubble of an UNRWA aid supply depot hit by an Israeli airstrike in May 2025. (Getty)

A UN worker amid the rubble of an UNRWA aid supply depot hit by an Israeli airstrike in May 2025. (Getty)

Even that assistance came to an end in May, however, when Israel replaced the UN’s operation with the new, joint US-Israeli Gaza Humanitarian Foundation. Since then, hundreds of people have been killed, by Israeli troops and armed private contractors, while trying to access the limited aid on offer at the foundation’s facilities.

But when it comes to its traditional negotiating role, let alone any question of putting the blue helmets of UN peacekeepers on the ground between the Palestinian people and the Israeli army in Gaza, the UN has remained conspicuously silent.

Whatever the will of the majority of its 193 member states might be, Washington’s unwavering commitment to support Israel, plus the power of veto granted to the five permanent members of the Security Council (China, France, Russia, the UK and the US), would block any such move.

During a press conference following the start of the 80th session of the UN General Assembly on Sept. 16, the day Israel’s fresh assault on Gaza City began, Guterres declined to say whether he agreed with the UN Commission of Inquiry’s conclusion that Israel was committing genocide in Gaza.

It was not, he said, “in the attributions of the secretary-general to do the legal determination of genocide. That belongs to the judicial entities, namely the International Court of Justice.”

He was then asked whether it was time for the UN to push for the deployment of a force to protect civilians in Gaza. His reply exposed the fundamental impotence of the UN, both in the face of the newly emerging world order, and the perennial issue of the UN Security Council’s veto deadlock.

“I do not think it will be possible to have a force at the present moment,” Guterres said.

“It will be rejected by Israel and then, I believe, rejected by also the United States.”

His preference, he added, would be for “an immediate ceasefire” and then to have “an international force able to protect civilians, (but) with the attack that took place in Qatar, it doesn’t look that Israel is interested in a serious negotiation for a ceasefire and release of hostages.”

On Sept. 9, Israeli forces conducted an airstrike on a government complex in Doha where Hamas leaders had gathered to discuss a ceasefire proposal. Six people were killed but the Hamas leadership survived.

It is striking that in President Trump’s Gaza peace plan, announced on Sept. 30, the only role envisaged for the UN was the distribution of aid.

Gowan said that within the UN, “the frustration with the Israeli campaign in Gaza is really profound. There is a sense that Israel is quite deliberately looking to end the UN as a factor in its neighborhood, and in its relations with the Palestinians.

“It’s fairly obvious that Israel is treating sidelining the UN as a de facto war aim. There is a very real sense among a lot of UN members that if Israel succeeds in this, then that creates a crisis for the organization because for so many UN members there’s always been a sort of fundamental belief that the organization has a particular responsibility to resolve the Palestinian question.

“The fact that the UN is being marginalized by Israel, with US cover, cuts to the heart of what a lot of member states believe is one of the overarching responsibilities of the organization.”

But as with so many issues in the world at the moment, from tariffs on trade to culture-war clashes, critical voices have been muffled for fear of offending the current administration in Washington.

“Privately, a lot of diplomats are stunned by the extent to which the Israelis have been willing to pursue a campaign that obviously has awful human costs, but is also just contrary to pretty much all the rules of diplomacy through the UN system,” said Gowan.

“There is a common sense of horror in New York. But talking to diplomats over the past year, a lot say, ‘We think this is untenable, but our capitals are very nervous about challenging Israel and the US over Gaza.’

“Countries are really torn between of this sense of responsibility to the Palestinians and their concerns about what taking a stance will mean.”

“International cooperation is straining under pressures unseen in our lifetimes.” Antonio Guterres speaks ahead of the UN’s 80th General Assembly in September 2025. (Getty)

“International cooperation is straining under pressures unseen in our lifetimes.” Antonio Guterres speaks ahead of the UN’s 80th General Assembly in September 2025. (Getty)

During his press conference on Sept. 16, Guterres made no bones about the scale of the crises the world is facing.

“We are gathering in turbulent, even uncharted, waters: geopolitical divides widening; conflicts raging; impunity escalating; our planet overheating; new technologies racing ahead without guardrails; inequalities widening by the hour,” he said.

“And international cooperation is straining under pressures unseen in our lifetimes.”

The gathering in New York of nearly 150 heads of state for the 80th General Assembly was “an opportunity we cannot miss,” he added. “UN week offers every possibility for dialogue and mediation, every opportunity for forging solutions.”

But behind the fluttering flags and the inscrutable glass facade of the UN building in New York, the organization now faces its own internal crisis, as thousands of employees begin to empty the contents of their desks into cardboard boxes.

“You have never seen the morale of the Secretariat at such a low point, certainly not in many, many decades,” Chen said.

“Staff unions are in open revolt. A lot of senior leaders are pushing back against the UN80 Initiative.

“Right now, I think the secretary-general is probably one of the loneliest people in the world. He sees all these global challenges arrayed in front of him but he’s really unable to do very much about it. He has nobody backing him, in terms of staff, in terms of member states.”

Some of this “is certainly his fault,” Chen continued. “There are some poor decisions that he made, some gambles he took, including on the UN80 Initiative. But there’s a lot of things that are certainly not his fault.”

Soon, however, none of this will be Guterres’ problem. The former Portuguese prime minister took office at the UN in January 2017, and his term will conclude at the end of 2026.

“As always happens when you enter a lame-duck phase, people are looking ahead and they’re saying, ‘Well, the next person is going to have to take responsibility,’” said Gowan.

Exactly who that next person might be “is an open question,” he added.

“Until Trump’s return to office, the conventional wisdom was that it should be a woman — we haven’t had a female secretary-general, ever — and due to the way that the UN rotates senior posts, probably someone from Latin America or the Caribbean.”

Until this year the presumptive front-runner was Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados. She is “a very strong performer on climate and development issues,” Gowan said. “But since Trump’s return to office, this conventional wisdom has been flipped … she is very much seen as being part of the global left.”

Other possible candidates, Gowan said, include Argentine diplomat Rafael Grossi, who has been head of the International Atomic Energy Authority since 2019 and “is campaigning very hard on the basis that he’s someone who can talk to Putin, who can talk to Trump, and can talk to Xi Jinping,” and Rebeca Grynspan, a former vice president of Costa Rica who is secretary-general of UN Trade and Development.

“There is definitely a sense that it’s time for new leadership,” Gowan added. “I think Guterres has been profoundly unfortunate, and I actually have quite a lot of sympathy for him because he’s a very thoughtful person and he sees problems, like the global regulation of artificial intelligence.

“But he has been faced with an appalling run of bad luck, having to deal with Trump 1, COVID, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, Gaza, and now Trump 2. I’m sure that right now Guterres is personally very frustrated, but basically just trying to balance the books and keep the UN afloat for his successor to arrive.

“In private, he’s been honest that he can do the cost-cutting bit of UN80 but, even if he throws out some ideas for bigger institutional reforms around the whole system, such as merging UN agencies or other really big institutional shake-ups, he doesn’t have the time in his last year to deliver these.”

Reforms are clearly necessary, Mudallali believes, “to bring the UN up to date, to make it more fit for purpose. They really have to align this organization’s purposes and processes with the modern world.

“They need to streamline it and make it more agile and more responsive, to make it appealing to member states. The bureaucracy is very big; you cannot still do things today the way they were being done when this organization was created.”

But the burden does not rest on the UN’s shoulders alone.

Nov. 13, 2023: the UN flag in New York flies at half-mast to commem orate the deaths of colleagues killed in Gaza. (Getty)

Nov. 13, 2023: the UN flag in New York flies at half-mast to commem orate the deaths of colleagues killed in Gaza. (Getty)

“The most important thing that will help the UN is if the member states and the great powers empower it and defend it,” she said.

“How could we let what happened in Gaza happen to the UN? Their staff were killed, their offices raided and destroyed. The UN should be sacred. Nobody should touch it. But if we start letting this happen, everyone around the world is going to do it.”

Member states, she said, “have the responsibility to protect this organization, to protect its functions, to protect its staff and to protect its mandate. It’s important to show that this organization represents us all and if you touch it, you’re touching the whole world.”

The UN is a large, multifaceted organization and some parts of it are likely to remain immune to whatever comes next.

“The UN is already a network of dozens of more-or-less autonomous organizations, some of which are getting along just fine,” said Gowan.

“There are parts, such as the International Telecommunication Union, and the International Atomic Energy Agency, whose finances are not hugely affected by the US cuts.

“You also have quite a lot of technical agencies, especially in Geneva and Vienna, that continue to set standards and act as clearinghouses for cooperation on the wiring of globalization — telecommunications, intellectual property, civilian nuclear use — and they, too, are immune from some of the crises in New York.

“Those technical agencies will continue to function — no one is really against having a Universal Postal Union; everyone likes post — and some of those technical agencies provide services that, really, no one else can.

“But I think there is a version of the UN 10 years from now in which the bits that we concentrate on — the Security Council, the General Assembly — could end up becoming relatively dormant.”

Meanwhile, Guterres is pressing ahead with the three major reforms that might, or might not, see the UN through to its centenary in 2045. The first two are under way: improvements to internal efficiency and a major review of the 4,000 mandates that underpin the work of the Secretariat.

But it is the third stream of reforms, exploring “whether structural changes and program realignment are needed across the UN system,” that promises potentially to deliver the most dramatic upheavals.

In reality, no one could attempt to argue, with any credibility, that the UN does more harm than good. As the organization pointed out in June, as it defended its record while simultaneously explaining the need for reform: “Right now, the UN assists over 130 million displaced people, provides food to more than 120 million, supplies vaccines to nearly half the world’s children, and supports peacekeeping, human rights, elections, and climate action across the globe.”

But as the UN knows only too well, and to its cost, in the world of today, optics can be more influential than facts.

And if a metaphor were required for the perception of an organization that is badly in need of an overhaul, it was perhaps delivered to perfection by the failure of an escalator as soon as the US president stepped onto it when he arrived to berate the UN.

President Trump, with his wife Melania, was not amused when a UN escalator failed him. (Getty)

President Trump, with his wife Melania, was not amused when a UN escalator failed him. (Getty)

It did not matter that the failure of the moving staircase was caused when a member of Trump’s own team inadvertently triggered a safety shutdown. Not did it matter that a teleprompter that failed during his speech was being operated by his own people. All the world saw and heard was the American president heaping all of the blame on the UN.

“All I got from the United Nations was an escalator that on the way up stopped right in the middle,” he said. “If the first lady wasn’t in great shape, she would’ve fallen. But she’s in great shape. We’re both in good shape, we both stood.

“And then a teleprompter that didn’t work. These are the two things I got from the United Nations: a bad escalator and a bad teleprompter.”

There is, of course, one benefit the entire world has received from the UN, and which was the whole point of creating the organization in the first place.

“We have to be optimistic,” said Mudallali. “So far, the United Nations has managed to help the world to avoid a third world war, and that is a very important thing.”

Credits

Writing & Research: Jonathan Gornall, Gabriele Malvisi, Sherouk Maher

Editor: Tarek Ali Ahmad

Creative Director: Omar Nashashibi

Graphics & Design: Ador Bustamante, Douglas Okasaki

Copy-Editing: Liam Cairney

Editor-in-Chief: Faisal J. Abbas